Tracing Scotland’s Neolithic Civilization Back to Armenian and Sardinian Roots

A watercolor drawing, signed John Frederick Miller, based on his pen and ink sketch of the Stones of Stennes, 1772. In Lysaght, A.M. (1974) Joseph Banks at Skara Brae and Stennis, Orkney. Notes and Records of the Royal Society of LondonBy Freddy Silva Archaeology & Science 2

Around 5300 BC a revolution occurred on Orkney. A group of unnamed astronomers and seafarers dared to sail across one of the most hostile waterways in the world to establish the earliest stone circles in the British Isles, along with unusual conical towers and horned passage mounds. Such architecture had no parallel in Britain, it had more in common with regions around the Caspian Sea and the Mediterranean.

When the first Scandinavian settlers arrived in Orkney, they recorded how the builders of this megalith culture were physically different from locals, spoke a different language, wore white tunics and behaved like a priestly caste, they formed a society apart, but by the time new settlers arrived they had long vanished. All that remained were their names: the Papae and Peti. The origins of these mysterious people and the monuments they left behind, from Orkney to the Hebrides and into Ireland, aroused my curiosity for years.

Axis Mundi Of Neolithic Orkney

Three stone circles form the axis mundi of Neolithic Orkney. The first, Stenness, is perhaps the most impressive despite only three-and-a-half of its 11 original monoliths remaining. Unlike others of its kind, Stenness looks and feels like a machine or a place of high council rather than an object with which to measure the sky, and it was still remembered as such before the town of Kirkwall took over the role. While looking through the notes of Joseph Banks’ expedition of 1772, I came across a watercolor of a nearby monument that has escaped everyone’s attention. In the foreground, a man sits on a broken stone drawing two megaliths, one leaning on the other, while a further six stones as tall as Stenness stand behind him. There is no mistaking the position and orientation of the illustrator, he is on high ground, with Stenness itself, now merely a semi-circle, positioned in the background with the loch beyond. Between the watercolor and the accompanying survey, one is given the impression of a quadrangular stone monument, and if so, the design seems consistent with similar enclosures such as Crucuno in Carnac, Avebury in England, and Xerez in Portugal, all of which were designed to calculate the extreme rising and setting of the Sun and Moon.

Along the narrow isthmus to the northwest of Stenness stands a more intact Ring of Brodgar, with 27 of its original 56 sandstones still upright (the number required to calibrate the solar and lunar cycles, just as with the Aubrey Holes around Stonehenge). The circle and its 12-foot-deep (3.6 meters) circular ditch were placed not on the high point of the ridge, as expected, but precisely where the 59th degree of latitude runs through the center.

Further along the ridge there is a third circle ignored by practically everyone, the Ring of Bookan, which occupies the high ground from where it is possible to see the other two sites. All that remains of Bookan is a central mound with a collapsed chamber and a circular ditch filled with soil. However, when Frederick Thomas visited the site in 1848, he clearly mentions several stones buried around the perimeter, since scavenged for building material; three are still employed nearby as gate posts.

Little written information survives on this collection of circles, only folklore. As for age, the earliest C-14 dating of debris from the ditch at Brodgar is 3700 BC, but this only informs us when the site fell into disuse and began to silt. The general archaeological consensus is that Bookan itself was likely built circa 4500 BC, fell into disuse by 2900 BC, and was thereafter monumentalized for the interment of human remains. When George Petrie assisted in the excavation of the site in 1861, he too was skeptical of Bookan having been originally used for burial, for a number of valid reasons, and that the orthostatic box he sketched inside the collapsed mound had served a very different purpose.

Since the ancients are known to have built many, if not all, sites according to the rules of sky-ground dualism — whereby the direction or layout of a monument memorializes an important moment in the sky and transfixes it on the ground — I decided to look into the near-straight alignment of the three stone circles and see if an archaeo-astronomical date could be established.

Alignment Of The Three Orkney Stone Circles

The alignment of Bookan, Brodgar and Stenness follows a general south-easterly trajectory of 129 degree. Plotting the coordinates gives a potential correspondence to the winter solstice sunrise circa 6800 BC. This was surprising because no one should have been building such structures this early and so far north, even though one local archaeological site has provided a radiocarbon date for human activity around 6600 BC. Looking closer, the three sites are not in perfect alignment – Stenness is askew from the others, or seen in reverse, Bookan is off-kilter. Any alignment is therefore redundant, and the answer lies elsewhere.

Were the Anunnaki the Architects of the Towers and Tombs of the Giants of Sardinia?

The Mystery of the Stone Monuments in Northern Scotland: Domains of Ancient Lunar Astronomers?

The Power of Sound Rediscovered in Prehistoric Barrows and Coves

It was at this moment that a vivid snapshot of the belt stars of Orion presented itself in my mind. Could this be what the architects had intended? Between Bookan’s strategic vantage point, Petrie’s sketch of its orthostatic box (giving us a useful angle of alignment) and its line of sight pointing to a natural bowl along the horizon formed by the interweaving of natural landscape features, we are offered a site pointing to a hollow from which a celestial object is supposed to rise.

While I waited for calculations to run their course on my laptop, I overlaid an accurate survey of the three pyramids over the Orkney stone circles and was surprised to see the same spatial relationship is consistent between the two sites, right down to the tip of each pyramid referencing the centre of each circle. This was very encouraging. Now all that was required was a marker in the sky above Orkney.

The typical markers for sky-ground temple relationships fall disproportionally on two specific times of the year: the winter solstice and the spring equinox. Tracking the sky back 8,000 years revealed that the Sun and the chamber of Bookan were never designed to meet. The Moon, on the other hand, is referenced at its Major Standstill when it makes a brief appearance a few degrees above the horizon. But what of Orion?

As the program slowly rotated the heavens in the era of 6600 BC – the earliest known sign of human activity in this region – Orion still lay below the horizon, so nothing doing there. Then on the evening of the winter solstice in 5300 BC, the three belt stars rise for the first time above the only available window, cutting a narrow arc over the island of Hoy for a brief 30 minutes before sliding behind the hills. So this is what the light box at Bookan was looking at so long ago.

But Orkney’s ancient architects had something more on their mind. The smaller of the three belt stars, Mintaka, is seen on the right. On the ground, the circle of Stenness is the smaller of the three and is therefore assumed to be the terrestrial counterpart of Mintaka. Taking a bird’s eye-view looking south, Orion’s Belt is seen mirrored in reverse by the three stone circles – a sky-ground relationship of which any ancient Egyptian would be proud.

The Orkney archipelago has been called the Egypt of the North on account of the disproportionate number of Neolithic sacred sites – 3,000 at last count – relative to its territory. The closest comparative example is Malta. Incidentally, a southward trajectory of 126 degrees through Brodgar and Stenness leads you directly to Giza.

Orkney’s Horned Mounds

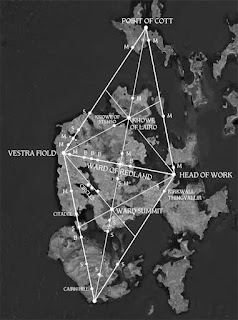

Across the archipelago one finds something truly alien to the region: horned passage mounds. The northernmost is Point of Cott, now partially devoured by rising seas, its 24-foot (7.3 meters) long orthostatic box more at home in Sardinia than Britain, its alignment matching the first ever rising of Orion’s Belt on the winter solstice circa 5300 BC; Head of Work lies in the east, its chamber marking the equinox sunrise circa 5000 BC; and finally the heavily weathered horned mound at Vestra Fiold, not far from where the stone for the circles was quarried. The dates make them contemporaries of the stone circles. As I marked them on an OS map, the three form a perfect isosceles triangle. I couldn’t help bisecting the corners to see what might lie at the center. The exact crossing point occurs on the island of Ramsay, at the base of a steep hill marked by Knowe of Lairo, a 130-foot (39.6 meters) long horned mound with a tripartite chamber.

It is quite an effort to position four remote objects accurately using GPS alone, but to do so without technology across 340 square miles (547 kilometers) of undulating terrain, over waterways, and with hills blocking your line of sight is impressive.

The Orkney Triangle and its mirror, with ground markers revealing its construction (Image: © Freddy Silva)

Maeshowe

Orkney’s other oddity is the splendidly preserved passage mound Maeshowe, predictably catalogued as a burial mound despite the absence of human remains. Architecturally the inside of Maeshowe shares more in common with passage mounds of Mycenia and the kurgans of the Black Sea region than it does with Scotland. Kurgan derives from the Armenian kura-garq, ‘crucible of the social class’, which in the context of a circular building denotes a meeting place for high-ranking people – a select priesthood, if you like. The variant kura-grag (‘crucible of fire energy’) implies an astronomical connection and ties in nicely with the alignment of Maeshowe’s passageway. However, anyone hoping to see the setting midwinter Sun align with the rear niche will be three weeks too early to witness it, thanks to the effects of Precession.

Crouching inside the passage affords a selective view of a horizon formed by the Orkney lowlands and the gap between the slopes of Ward Hill and Knap of Trowieglen on Hoy, essentially suggesting a bowl into which an object descends. Taking the earliest C-14 date of the mound at face value, it would have been 3990 BC when the midwinter Sun was seen descending into this bowl, followed by the Moon at its Minor Standstill, consecrating the cosmic marriage of masculine and feminine. But there is more. On that same night, Orion’s Belt is seen descending into the same bowl, a performance repeated once more on the spring equinox. The date implies Maeshowe was a later addition to the area, as proved by the discovery of an earlier stone platform with sockets for two massive stones, around which the mound was erected.

The surprise here is that ancient people rarely, if ever commemorated or celebrated the setting of objects in the sky, but rather their rising or mid-heaven positions, when the energy and power of such ‘gods’ were deemed to be at their most abundant. Much in the same way no one celebrates an empty glass of Scotch. This glitch at Maeshowe has been bugging me for years, leading me to speculate that the mound’s reference to the setting Sun and other celestial objects must have been important to people for whom this was culturally significant, and as far as I am aware, the Egyptians and Armenians are the two rare cultures known to do so.

Domain Of Noble People of Orion

Archaeological, genetic and archaeo-astronomical data suggest the ancient architects bypassed mainland Britain and arrived first in Orkney, then followed east towards the Outer Hebrides. Hebrides is a corruption of Hy Bridhe, ‘Isles of the Brides’, possibly in commemoration of the Gaelic goddess Bridhe. Another possibility rests on the movement of language, with Gaelic having evolved from Indo-European regions, specifically Asia Minor, with elements of Egyptian. With Armenian language as the root, the word bryge was applied semantically to an elevated or illustrious class of people who originally migrated from the Armenian Highlands to western Europe; hy, on the other hand, is a contraction of hye, a person of Armenian origin, which itself derives from hayk, the Orion constellation. Thus, to an Armenian visitor, Hye Bryges ostensibly means ‘domain of noble people of Orion’ or ‘domain of noble people of Armenian origin’. This may explain the Gaelic term for the Hebrides, Inse Gall, ‘islands of the strangers’, most likely given to a people arriving from afar of sufficiently contrasting physiognomy for it to be memorialized.

The Gateway of Callanish

Stone circles and standing stones are also a feature of the Outer Hebrides, the Isle of Lewis in particular. Just as Brodgar and Stenness are both located on major fault lines, so the impressive stone circle and cruciform stone rows of Callanish, along with its attendant sites, cluster within an extremely strong gravity anomaly zone, while the circles themselves delineate a localized region of low natural magnetism. It is therefore odd that amid such meticulous calculation, the ancient architects chose to place Callanish where a prominent crag by the name of Cnoc an Tursa blocks an otherwise uninterrupted 360-degree view of the horizon. Looking at Callanish from afar, it becomes clear that the circle and its central monolith are deliberately using the mound-shaped crag, least of all because sockets for the missing stones are located there, along with a large back-filled socket for a stone whose scale would have created a focal point in itself.

I recalled the stone circles of Orkney and how they mirror the first rising of Orion’s Belt on the winter solstice circa 5300 BC. No such association has ever been explored at Callanish, but if made it would establish a coherent pattern of behavior by the elusive architects. Standing inside the circle, looking down the southerly row of stones towards Cnoc an Tursa, Orion’s Belt rose for the first time above the crag on the winter solstice circa 5000 BC.

At the same moment, looking back at the opposite end of the avenue, which aligns to the celestial pole, the bright star Vega appeared above the stones. The same dual relationship presents itself at another striking ancient monument 2,500 miles (4023 kilometers) away in the region that used to be ancient Armenia – the enigmatic Stone Circle D at Gōbekli Tepe – the difference being that it took place there 5,500 years earlier.

Dun Carloway

Be that as it may, the most unusual monument in this region is neither a megalith nor a stone circle. A few miles north of Callanish stands a tapered stone tower at Dun Carloway that, like others of its kind, has vexed historians for centuries because these iconic structures are unique to Orkney, Shetland, the Western Isles and the tip of northern Scotland. To quote one: “It means that we have here the remains of a period of architectural activity which has no parallel in the early history of our country.”

Dun Carloway has been used, reused and adapted over time. It is built of well-fitted stone without mortar. The central courtyard is surrounded by a hollow wall, inside which a staircase winds its way to where there used to be upper galleries. From what remains of the structure, windows appear to have been sparse. The tower incorporates features far and beyond what is necessary in a residence. For example, the design is based on music ratios: its external to internal diameter conforms to the octave; the wall from north to south varies in thickness by Pi; the main door is framed to a ratio of 1.33:1, equivalent to the note F. It is as though the residence was intended for a musician or a mathematician.

Or an observer of the sky perhaps? The entrance is impractically placed to face the most windswept direction off the ocean yet faces a pointed rock ledge which references the Minor Lunar Standstill as well as the Cross quarters – the midpoints between solstices and equinoxes that mark the beginning of seasons in the Celtic calendar. All this specialist information seems far beyond the everyday requirements of eating and sleeping.

There is evidence of people living here in 100 BC, but if the tower was meant to offer long-term protection from raiders (the other explanation), the fact that it could shelter no more than a dozen people and animals comfortably, and had no access to a well or sewage disposal, means that two weeks of siege by half a dozen pirates was all the effort required before the besieged began to look at urine as fine wine or to each other as a source of nourishment. There is also the problem of the tower standing 50 feet (15.24 meters) lower than the adjacent bedrock. As any military strategist knows, if you do not own the high ground the outcome will not be positive. Perhaps the tower, like the ancient monuments around it, was inherited from an earlier period and re-used by different people with different needs?

The Nuraghe of Sardinia

A trip to the Mediterranean island of Sardinia reveals 6,500 towers resembling Dun Carloway, each with traditions associating them with astronomers and seafarers, very tall ones at that, who migrated here over 8,000 years ago from the Armenian Highlands and left their genetic footprint in the present population. These nuraghe lent their name to an entire civilization, and yet no one can satisfactorily explain where this word came from or what it means.

Many nuraghe can comfortably house no more than four people and have no access to water, making them useless as fortifications; certainly, they were not cost effective. However, their low entrances, dark interiors, and narrow windows focused on the artificially flattened summits of nearby hills are all indicative of observatories. Indeed, one such observation at nuraghe Ruju and Santu Antine allowed me to calculate the first to mark the rising of Orion and Sirius out of the summit on the winter solstice in 6000 BC, then watching their trajectories descend into the next flattened summit, as observed from the window in nuraghe Santu Antine.

And just as Bookan is the odd one out in Orkney, so in Sardinia the Ruju-Santu Antine alignment is completed by the passage mound of Sa Coveccada, forming a straight line, with the third site offset by two degrees, altogether mirroring the belt stars of Orion — as they appeared above Sardinia at mid-heaven in the era of 6000 BC.

Sardinia is also home to horned mounds, possibly the oldest in existence. They are classified as tomba di giganti except no giants’ remains have been found inside these orthostatic boxes that once were covered with soil, just like the Orkney mounds. Instead, the remains of very, very tall people have been found all over the island in common graves. A cursory investigation into the alignment of these horned mounds indeed finds them all predating those on Orkney by as much as 2,500 years, with many marking the rising of Orion on the winter solstice beginning 4000 BC, through 5200 BC, with the site at Iloi marking its mid-heaven position in 7200 BC, and Li Loighi and Imbertighe establishing the oldest correspondence on the equinox of 8500 BC.

The Importance of Etymology

Now it gets interesting. As language and people moved westwards from Armenia into the Mediterranean, towards the islands of Malta and Sardinia, the Maltese word nur is traced to Azerbaijan (what used to be old Armenia), its aggregate meaning being ‘just or rightful, light or shining person’. Classical Armenian offers specific details about these rightful people. The word nuirag refers to a ‘holy representative or legate’, from which derives nuyral (devoted). Altogether, the nuraghe of Sardinia are best described as places of ‘the rightful, white, shining, holy representatives. Incidentally, the Armenian solar god Ardi was wedded to the goddess Sel-ardi, and as the name migrated it took on the shorthand form S’ardi, as in ‘belonging to Ardi’, from which developed Sardinia, ‘the land of the bride of the Sun’.

This overlap of values between ancient Armenian culture and Sardinia, along with people clearly attached to Orion, led me to examine the names of Scotland’s sacred places. Put through Armenian etymology, the tower Dun Carloway is best broken down as: dun (dwelling) or dohm (a noble race or family); and Carloway: kar (stone), ogh (ring or circle), e’ag (being, existence), forming Dun Kar-ogh-e’ag, ‘existence of the circular stone dwelling of a family of noble race.’

Orkney is best defined as ar-kar-negh (narrow stones of the god), a possible reference to the visual quality of Stenness. That seat of council Stenness (or the earlier Stenis), comes up as tses-nisd (place of ritual) and s’tenel-nish (to place a mark). But the Egyptian equivalents are even closer to the mark: s-ten-nes (to arrive at a distinguished place), and seh-t-en-nes (to approach the place of council).

Perched on high ground, the Ring of Bookan or Bukan forms the tail of a string of circles. In Armenian, poch’-gah means ‘tail stones’. The Ring of Brodgar, or Brogar, is described in local folklore as a place where giants danced to music and were turned to stone. It’s Armenian equivalent, barerq-kar means ‘dance song stones’. However, there is an even closer Egyptian root: b-ra-gah, ‘abode or shrine of the Sun god’.

Looking like a place of council across the way, Maeshowe appears as marz-hay (pronounced mez-hui), the ‘province or domain of Armenians/Orion’. Bringing the Armenian god Ara into the equation, where, depending on the context, the root ar means ‘assembly’, ‘creation that connects to light’, ‘nobility’, ‘power’ and ‘sun’, we can take the variant mes-ar to mean ‘great assembly of nobility’ or ‘great assembly of the sun’.

Turning to the stone circles of Lewis, we find Ceann Hulavig’s original Gaelic name Sron A’Chail to originate from the Armenian srah achk-aha, ‘the room of seeing’. The summit of Callanish is marked by that protruding outcrop Cloch an Tursa, where tur-sar literally means ‘door or gateway to the summit’.

As for Callanish, it was so good they named it twice. The first Armenian interpretation remains almost intact: kar-nish (a stone marker), along with the variants kharag-nish (rock cliff marker), and khachanish (to mark or cross). The site’s Gaelic name, Tursachan, is explicitly referenced as tur-sa-quah (doorway to the stone seat or throne), although a visiting Egyptian might expand on this with Ta Ur S-aqer, ‘to make perfect the great land of the gods’.

The Papae And Peti

But who might these gods might have been? The only surviving reference to the ancient architects are their names: Papae and Peti. The Peti of Orkney were considered to have been the original settlers, described as “people of strange habits” who spoke a different language. Both the Peti and Papae were associated with abodes of a sacred nature and wore long white robes, the kind of garment typically identifying a priest or sage in ancient temple tradition. Perhaps one group mapped the sky while the other attended to stonemasonry and monuments, anchoring the calculations to the land. Such a division of roles was common in the temple raising practices of ancient Egypt, and an examination of these people’s etymological fingerprint reveals a definite intertwinement. Access to the Egyptian temple was restricted to the learned, the purified and the initiated, qualities reflected in their white robes of office, and the nickname petriu, ‘those who see’, visionaries, initiates with more finely attuned faculties, precisely the kind of responsible individuals one wants in charge of a sacred environment.

The related term petiu is even closer to the Scottish name. It means ‘heavenly beings’, while the derivative petr means ‘a region of sky’, so clearly the petriu or petiu, and by extension the Peti, were involved with understanding the stars and their shamanic potential. Elegant and puissant, they were referred to by Persians as peri, whom they described as tall and graceful people possessing the gifts of clairvoyance and the ability to walk between worlds. The name followed them to Ireland where it was modified to reflect the local tongue as Feadh-Ree.

The name Papae, on the other hand, comes from the Armenian p’apegh, a monk or holy person. Its diminutive pap denotes ‘a grandfather or elder’, while the extension papenakan means ‘inherited from ancestors’. If the picture painted here is correct then we are presented in Orkney, the Hebrides, and Ireland too, with a priestly class possessing an ancient inherited knowledge handed down from an established yet remote culture, and as early chroniclers correctly noted, they were not local. As from where these strangers might have originated, on the basis of modern population samples, one genetic group migrated from the Balkans via eastern Scotland, while Y-chromosomal evidence suggests a second group migrated up to 3000 BC from Iberia to the western and southern British Isles, contributing 24% of modern genetic lines. But perhaps the most telling study concerns the DNA of Scotland’s highly diverse people, which pinpoints their origins in Siberia, Arabia and Egypt.

Extract from Scotland’s Hidden Sacred Past.

Freddy Silva is a best-selling author of ancient civilizations, earth mysteries and ancient systems of knowledge, with six published works, including Scotland’s Hidden Sacred Past.

https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/orion-0

Hunting With Clovis Spears

Once here in the Americas, the people invented the Clovis Point, which is considered to be the first American invention. It was a fluted spear point whose sheer beauty has never been rivaled. Because the first example of this point was found near the town of Clovis, New Mexico, the people who made it were called Clovis people. For a long time, and in many corners of the archaeological world even today, they were called the First Americans. In the 1960s it became popular to declare with great confidence that these people, armed with their wonderful invention, were the ones who hunted the great mastodons to extinction. Their arrival seemed to coincide with the disappearance of the great beasts, so why not? It was a great theory back then, partly because the urbanization of America had led a lot of people into cities and hunting was becoming a sort of social stigma.

But to read those articles now, they seem illogical in one respect. One moment the author is saying how risky and difficult it was to take on a mammoth. Paragraph after vivid paragraph talked about the danger. National Geographic was hugely popular in those days, partly due to beautiful and vivid artist's renditions of a supposed mammoth hunt, showing modern man’s brave ancestors surviving by bringing down great, lumbering beasts, sometimes at the expense of their lives. But then, after showing how hard it was to kill a mammoth, the same authors would blithely move on to say that mammoths were hunted to extinction all across the breadth of North America because the great beasts were so unused to people that they just stood there and let people walk up and throw one of their Clovis-tipped spears into their sides. Down they went, victims of superior technology. The two contrasting pictures never quite made sense. But a lot of people bought it. Those were simpler days.

While this theory was being touted about and written up in high school textbooks, however, the information that giant sloths, huge beavers, immense bison, saber-toothed cats, dire wolves, short-faced bears, and even a type of spruce tree, went extinct at this same time was quietly suppressed. To advertise this information would serve to weaken the whole Clovis First theory. After all, why would a hunter seek to bring down a spruce tree with a Clovis point?

Coming To America

Today, though, it has become untenable to stick to Clovis First. Did people cross into the Americas by way of Beringia? Unequivocally, yes. But was Beringia the only geographical area to put out a welcome mat? Certainly not. Then as now, America seemed to be a melting pot, open to immigrants from all over. They walked in on foot, they came here by boat, they followed coast lines, they explored rivers, and generally took advantage of a land consisting of two continents that were rich in resources and opportunities.

But when did they start arriving? Who were the very first Americans? To close off any door but Beringia is to run smack into glaciers that did not start to melt until relatively recently. But to add boats to the equation or postulate an ancient time way back before the last Ice Age when Beringia was also open to foot travel, opens a lot of avenues of entry. The problem is that many archaeologists who based their life’s work on Clovis First do not want to allow their ancestors to be a lot older than is currently considered acceptable. Take away boats, take away age, one is stuck with Clovis First. Those ‘takeaways’ are too big a hurdle for many archaeologists to accept. "Where is the evidence?" they shout. "Show me some proof!"

Thus, the circular reasoning has run for almost a hundred years. "Clovis First is the gospel," says academia. "We are not going to waste money chasing a crazy theory. When you reach a Clovis layer, stop! Don't fritter away funds that could be used to do real archaeology." So, there it is. It is entirely possible that for almost a century there was little evidence to the contrary because the establishment had declared such evidence off limits. How can one accumulate evidence if one is not permitted to look for it? For almost a hundred years the public has been spoon-fed a mistaken theory. Those who dared to question the whole process were emotionally and financially bullied, sometimes driven right out of the field.

Footprints In The Sand

Now, thanks to sharp eyes and painstaking work, that evidence has come forth into the light of day in White Sands National Park in New Mexico, only 200 miles (321 kilometers) away from Clovis, the site that gave the Clovis Culture its name. The new evidence, consisting of thousands of 23,000-year-old human footprints scattered over some 80,000 acres, predates the Clovis Culture by more than 7,000 years.

One group of footprints consists of a single traveler, who walked in a straight line for a mile and a half. Others were made by energetic children, who ran from place to place, back and forth, while jumping up and down, as children will do. Yet another set of tracks clearly shows the place where an obviously tired mother placed her very young child down on the ground, presumably to gain a few minutes of rest.

The traditional argument against pre-Clovis sites is that most of the evidence so far has consisted of stone projectile points. Stone cannot be radiocarbon dated, so it's apparent age is determined by dating the organic soil in which the artifacts are found. If the scientist doing the examining chooses to follow the accepted archaeological, academic dates, it is easy to make the argument that somehow a 12,000-year-old projectile point could somehow have migrated to older soil by migrating down a fissure in the soil or somehow being buried under more ancient, carbon-based strata.

But when David Bustos, the park’s resource program manager, first spotted the footprints in 2009, and began to invite experts to the scene, it was obvious that something special was about to happen in the world of anthropology. The importance of the discovery was perhaps best summed up by Ciprian Ardelean, an archaeologist at Autonomous University of Zacatecas in Mexico: “I think this is probably the biggest discovery about the peopling of America in a hundred years. I don’t know what gods they prayed to, but this is a dream find.”

Evidence indicates that the footprints originally formed when groups of people traversed the damp, sandy ground on the margin of an ancient lake. When lake sediment slowly filled in the prints and the water receded, the ground finally hardened. Later, due to the slow but relentless work of erosion, the prints gradually resurfaced, until they were eventually spotted in 2009. Thanks to the invention of ground-penetrating radar, their entire three-dimensional structure can now be observed, including marks of heels and toes.

And humans were not the only mammals who left tracks on the ancient shoreline. Dire wolves, which may have been stalking the humans, camels and mammoths, which may have been stalked by humans predators, left signs of their presence. One set of prints even indicate where a giant sloth apparently saw a group of hunters coming, and quietly headed for safety.

Dating Grass

In 2019, Jeffrey Pigati and Kathleen Springer, research geologists at the United States Geological Survey, went to the White Sands site to explore. By this time the site itself was well-known to the anthropological community, but its age had not yet been determined. Clovis First still remained the academic doctrine, so no one had investigated to any great degree. But as the geologists searched the area, they discovered ancient blankets of ditch grass seeds that had grown by the lake. Grass seeds, which are organic, can be carbon-dated. The results of their tests came as a shock. The seeds came from grasses that had grown thousands of years before the last Ice Age.

Knowing that their find was controversial, the researches embarked on a far more compressive study. “The darts are going to start flying,” said Pigati, “so we better be ready for them.” They decided to dig a trench near one cluster of prints that contained both human and animal tracks. On one side of the trench, they found layers of grass seeds, forming thick blankets of sediment. Eventually six such layers were recorded, and 11 separate seed beds, the earliest testing out at 22,800 years old. In this sediment, firmly entrenched, with no possibility of the tracks migrating into the area much later, were the oldest footprints yet discovered, left by both humans and a mammoth. In other words, when these seed grasses grew on the shoreline of an ancient lake, almost 23,000 years ago, mammoths and humans lived side by side. The youngest dates were from 21,130 year ago, meaning that people visited this lake, hunting and gathering from its rich resources, for more than 2,000 years.

Time Stalks Everybody

But at this time of history, the northern glaciers were still firmly in control, blocking any human migration on foot down from Alaska, through Canada. So how did they get here? No one really knows for sure. They might have followed the shoreline, which was mostly free from glacial activity. They might have arrived by boat. They might have migrated north, from Central or South America, or even from the east, according to the Solutrean hypothesis that postulates migration by boat from western Europe.

Whatever their route, however, the evidence is now overwhelming that they got to New Mexico millennia before the Clovis First doctrine postulates. In the words of Ruth Gruhn, an archaeologist at the University of Alberta, “This is a bombshell. On the face of it, it is very hard to disprove.”

If humans were living in New Mexico 23,000 years ago, and stayed there for at least 2,000 years, they must have somehow entered the continent long before that. In the words of Dr. Sally Reynolds, of Bournemouth University: “That starts to wind back the clock.”

There are, of course, those in the scientific community who, while applauding the careful work being done at the White Sands site, refuse to accept the data without more confirmation. Science breeds fundamentalists just as religion does. But this adds further urgency to the research. Footprints, even those that are 23,000 years old, tend to start eroding once they see the light of day. When exposed, they are subject to wind and rain, just like rocks everywhere. The exposed footprints at White Sands are thus living on borrowed time. “It is kind of heartbreaking,” said David Bustos, who discovered the tracks in the first place. “We are racing to try to document what we can.” Time stalks everybody. The universal task is to do what is possible while the opportunity presents itself, even though the task began 23,000 years ago, on the shores of a lake in ancient New Mexico.

https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/clovis-first

The Lonely Stones That Square The Cosmic Circle

Both beneath and beyond Stonehenge in England, the Great Sphinx and Pyramid of Khafre in Egypt, Machu Picchu in Peru, Chichen Itza in Mexico and Newgrange in Ireland, exists an underlying code that binds the distant builders. Distant, in both space and time, yet the constructions are fused in that they were all built in honor of the quarters of the year, the two solstices and equinoxes. Today this data is available from apps at the click of a mouse, but in the ancient world, ceremonial standing stone circles and temples evolved from the earliest stone observatories, which themselves were designed to pin down the four observable corners of the cosmos.

At the very earliest stages of sky watching among the first observations that really mattered, in that they directly affected climatology and therefore survival, were the two equinoxes and two solstices. These four key astronomical events occur due to the way earth orbits the sun on its tilted axis, and while some may consider humankind’s ancestors as primitive, they had a much closer and experiential relationship with the cycles of the heavens. To overcome the apparent chaotic nature of the night sky a range of stone devices were created all over the globe that evolved into some of the greatest temples and monuments of the prehistoric world.

Ancient Astronomy Tool Kit

Ancient ancestors hacked a living in the raw and unforgiving outdoors and without books and televisions to distract them from the sometimes-mundane passing of time, they would often marvel at the cycles of the planets and stars, much more than is practiced today. Tracking the paths of the Sun, the Moon and the stars across the sky, they observed that the planet’s poles are inclined from the celestial plane, implying that two solstices occur bi-annually when the solar declination reaches the Tropic of Cancer in the north and the Tropic of Capricorn in the south.

Diagram of the earth's seasons as seen from the north. Far left: summer solstice for the Northern hemisphere. Front right: summer solstice for the Southern hemisphere. (Public Domain)

During the June solstice (June 20 to June 22) the solar declination is about 23.5°N (the Tropic of Cancer) and during the December solstice (December 20 to December 23), the solar declination is about 23.5°S (the Tropic of Capricorn). This means the solstices, and shifting solar declinations, result from the Earth’s 23.5° axial tilt, while orbiting the sun. The resulting summer or June solstice in the Northern hemisphere is the longest day of the year, when Earth experiences the maximum intensity of sun rays, therefore, it has the most hours of sunlight. The opposite is the case for the December or winter solstice which is the shortest day of the year with the least hours of daylight. The situation is reversed for the Southern hemisphere where the June solstice heralds the shortest day in winter and the December solstice falls in the high summer. In both hemispheres, from the March equinox it presently takes 92.75 days until the June solstice; 93.65 days until the September equinox; 89.85 days until the December solstice and 88.99 days until the March equinox.

Today, the two solstices mark the beginning of winter and summer, but this was not always the case in the earliest human cultures. An entry in the National Geographic resource library explains that some ancient cultures only recognized two seasons (there was no autumn or spring), so the solstices occurred in the middle of the season. This is why solstices are known as midwinter and midsummer respectively, and why since ancient times many cultures have marked the solstices with elaborate rituals and sacrifices, which evolved into celebrations and festivals and ended up as modern calendar holidays.

Midwinter Celebrations

Intuitively one might assume that the midwinter solstice represented misery, hardship and death, but many ancient solar traditions honored and celebrated the winter solstice, which despite occurring in the cold, winter season, indicated the return of light. All over the ancient world Northern hemisphere December solstice festivities emphasized light and with the winter solstice being the shortest, darkest day of the year, it also symbolized the beginning of newfound life, hope and future health.

Perhaps the most famous midwinter observatory, and later festival site, is England’s Stonehenge. This iconic ancient stone circle features the Heel Stone, which marks the June solstice sunrise. Every year on the June solstice thousands of people travel to Wiltshire, England, where the huge stone circle that was raised around 3000 BC becomes a focus for solar worship marking the relationships between the sun and the changing seasons.

The use of a single large menhir to mark the azimuth (angle) of solstice and equinox sunrises and sunsets was relatively common across the ancient world. This astronomical dynamic, code or device is also seen the at the Inca ruin of Machu Picchu, in the Urubamba Valley in Peru, where the Intihuatana Stone (hitching post of the sun) marks the December solstice. Furthermore, this stone is positioned so that each corner points towards one of the four cardinal points (north, south, east, and west). The location was a deeply sacred gathering spot where people observed the solstice sun and danced and prayed for their survival through the rest of the resource-threatening winter.

Intihuatana Stone at Machu Picchu (Machu Picchu) is associated with the Inca calendars, civic, ritual and agricultural. (CC BY-SA 2.0)

The midwinter solstice was celebrated in Ancient Rome with the Saturnalia festival, in honor of the god Saturn, that began on December 17 (Julian calendar) up to the actual solstice event around December 21, during which time the entire population of the empire, both rich and poor, went momentarily crazy, unbridled and pure feral. According to historian John F Miller in his 2010 book Roman Festivals during Saturnalia festivities, Romans enjoyed banquets, gambling, jokes, gifts, and a tradition “of usurping strict social structures,” for example, elites served food to their slaves. On a religious level, the earliest Christians celebrated Saturnalia for Advent and Christmas while Pagans and neopagans directed their celebrations towards the winter solstice as Yule. In both Pagan and Christian traditions people born on December 25 were thought of as having been born with the Sun and perhaps no better an omen could surround one’s birth.

Hadrian’s Hideout

Roccabruna at Hadrian’s Villa in Tivoli (Public Domain)

Eric Hand’s article published in Nature, titled The Emperor's country estate is aligned to meet the solstices explains that the Roccabruna at Hadrian’s Villa, located 30 kilometers (18 miles) east of Rome, was “a place where the Roman Emperor could relax in marble baths and forget about the burdens of power.” Dr Marina De Franceschini, an Italian archaeologist from the University of Trento in Italy, wrote a paper in which she credited two architects, Robert Mangurian and Mary-Ann Ray, for noticing a solstice light effect and that the villa's buildings are aligned so as to produce sunlight effects for the seasons. An example of these solstice angles in the architecture of the villa is that during the summer solstice, “blades of light pierce two of the villa's buildings on the summer solstice through a wedge-shaped slot above the door and illuminates a niche on the opposite side of the interior.” Furthermore, in a temple of the Academia building, De Franceschini measured the archaeoastronomy within the two buildings and discovered sunlight passes through a series of doors during both the winter and summer solstices.

Devoid of spiritualized meaning, in dry reality, the solstice and equinox events are but fleeting moments when a star emerges from and sets behind a horizon, until however, an architect or builder manifests the moment in stone. De Franceschini says that the two buildings at Hadrian’s villa are connected by an esplanade “that was a sacred avenue during the solstices which were linked to religious ceremonies associated with the Egyptian goddess Isis, who was adopted by the Romans.”

Archaeoastronomy in Egypt

In Ancient Egypt the summer solstice signaled the beginning of the new year, the peak of hunting activity, agricultural fertility, and the approach of the all-important harvest season. Therefore, midsummer festivals were celebrations of nature’s bounty and life-giving energies were personified in a range of solar deities. Sirius is the highest magnitude (brightest) star in the night sky and because it appeared soon after the summer solstice astronomers associated its annual appearance with the seasonal flooding of the Nile River, upon which the entire Ancient Egyptian civilization depended for its continued survival.

On the midwinter sunrise the Egyptians celebrated the rebirth of the god Horus and the celebrations lasted for 12 days during which time they decorated their homes with plants and vegetables to welcome in a prosperous and bountiful new year. On an archaeoastronomical level, an October 2020 Egypt Today article notes that “every year, scientists renew their interest in the astounding progress that the pharaohs of ancient Egypt reached in the field of astronomy, thanks to the sun alignment phenomenon, where the sun illuminates the face of Ramses II statue in Abu Simbel.” This occurrence was first observed at sunrise on December 22, 1874, and lasted only 20 minutes, but it was noted that “the sun-rays penetrated the entrance to the temple, until they reached a small room that contained a number of statues.”

Solstice Architecture in British Isles

In Scotland and Ireland around 3200 BC ancient farmers built huge stone mounds aligned with the solstices, for example, Maeshowe in Orkney and Newgrange in Ireland. The latter is a mound in the Boyne Valley, County Meath, Ireland, measuring 85 meters (279 feet) in diameter and 13 meters (43 feet) high, covering an area of about one acre. For five days around the winter solstice a narrow beam of light penetrates a roof-box above the front portal and it gradually extends to the rear of the chamber where it illuminates the entire inner chamber, dramatically, for about 17 minutes before the sun rises and the event ends.

Newgrange in the Boyne Valley is a 5,000-year old Passage Tomb famously designed in honor of the December solstice, at which time the passage and chamber were illuminated. (Public Domain)

Equinox Monuments In Mesoamerica

In Latin the word equinox means “equal night” representing the two days of the year when there are 12 hours of light and darkness, around March 21 and September 21. An article in The Old Farmers’ Almanac presents Chichen Itza in Mexico as a vast Mayan equinox monument, a huge pyramid built around the year 1000 AD that signals the beginning of the seasons. On the spring equinox the rising and setting sun animates the architecture when a serpentine shadow is seen moving along the edges of the structure on the Mayan festival day “the return of the Sun serpent.” During the spring and fall equinoxes the pyramid dedicated to Kukulcán (or Quetzalcoatl) serves as a visual symbol of the day and night. On every equinox, the sun of the late afternoon creates the illusion of a snake creeping slowly down the northern staircase. Symbolically, the feathered serpent joins the heavens, earth and the underworld, day and night. Seven shadow triangles on the side of the staircase connect the top platform with the giant stone head of the feathered serpent at the bottom. Like Stonehenge in England, thousands of pilgrims travel from around the world to Chichen Itza every year to witness this astronomical spectacle.

Angkor Wat Equinox Wonder

In ancient Cambodia at the Angkor Wat Temple when the Sun crosses the plane of the Earth’s equator and day and night are of equal length, the Khmer kings connected the Earth with the sky using extraordinary astro-architecture. The entire complex is aligned with the equinox and when the Sun rises and sets in the east and west respectively it does so over Angkor Wat's temple towers. On March 21 2021, the equinox festival held at Angkor Wat marked a special day and top number of 3 + 3 + 3=9. March: 3, 2+1=3, 2+1=3. Furthermore, in the Khmer language the Angkor Equinox itself, is “សមរាត្រីនារដូវប្រាំង” which means “Dry Season Equinox” for the March Equinox and “សមរាត្រីនារដូវវស្សា” meaning “Wet Season Equinox” for the September equinox.

Nabta Playa in Africa

Perhaps the tidiest way to wrap up an overview of the world’s astronomical marvels that all paid homage to the four quarters of the year, is a visit to the first astronomical site on the planet, Nabta Playa in Africa. This 7,000-year-old stone circle not only tracked the summer solstice and the equinoxes, but also the arrival of the annual monsoon season, just as the Mayan pyramid serpents and Angkor Wat’s temple towers indicated 6,000 years later. Nabta Playa stands some 1,126 kilometers (700 miles) south of the Great Pyramid of Giza in Egypt and represents possibly Earth’s oldest astronomical observatory ever discovered. It was constructed by a cattle-worshiping cult of nomadic people to mark the summer solstice and the arrival of the monsoons. Dr J. McKim Malville professor emeritus at the University of Colorado and an archaeoastronomer wrote in Astronomy that this site is “human beings’ first attempt to make some serious connection with the heavens” and he added that this site also represents the dawn of observational astronomy. Dr Malville experienced an epiphany when he discovered that this remote sand blasted stones formed part of an alignment that radiated out from a major tumulus.

What did the first sky watchers think about what must have been exceptionally mysterious lights in the sky? Mysterious, in that they followed patterns that could be replicated on earth, and in these shapes the blueprint for all astronomy, architecture, design and worship evolved, as the square. But how exactly where the lights in the sky perceived? Surely, in an ancient, animated world, the stones themselves must have been considered as the gods’ consorts on earth? And those deep black shadows that were cast on the sunrises and sunsets on the two equinoxes and solstices might have been perceived as the gods themselves manifesting on earth, and it was along those shadows that ropes were pulled, and sacred stone sites and temples were raised in honor of the great cosmic square.

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. www.ashleycowie.com.

https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/archaeoastronomy

The Thule Culture: Medieval Mariners Migrating In Search Of Meteoritic Iron

![]()

The modern English word, ‘Thule’, first appeared in ancient Greek and Roman cartographic documents as the Latin word Thūlē, describing farthest north location in the known world. Over the centuries historians and archaeologists have variably concluded that word represented northern Scotland, Orkney or Shetland, but according to some researchers even the island of Saaremaa (Ösel) in Estonia and the Norwegian island of Smøla have been suggested.

Researchers Nieves Herrero and Sharon R. Roseman in their 2015 book The Tourism Imaginary and Pilgrimages to the Edges of the World write that in Classical and Medieval literature the term Ultima Thule (Latin: farthermost Thule) acquired a metaphorical meaning of any distant place located beyond the borders of the known world.

The meaning of the original Greco-Roman word Thule had evolved by the Late Middle Ages and early modern period when it was used to identify Iceland, and Ultima Thule generally referred to Greenland. By the late 19th century Thule most commonly identified Norway. In 1910, the explorer Knud Rasmussen, the so-called father of Eskimology, became the first European to cross the Northwest Passage with a dogsled and he named the missionary and trading post he established in north-western Greenland, Thule. It was later changed to Qaanaaq.

In modern history German occultists believed that the historical Thule, (Hyperborea) was the land from which the Aryan race originated, and the Thule Society was associated with the Deutsche Arbeiter Partei (DAP), known later as the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (NSDAP or Nazi party). Idiots.

Thule North Sea Migrating Mariners

While for some the word Thule may bring imagery of Nazi atrocities, to other it inspires images of ancient Greek explorers navigating the North Sea, exemplifying the ancient Thule or Northern Maritime culture. These prehistoric hunter-fishers emerged around 200 BC and lasted to around 1700 AD in the Bering Strait and along the Arctic coast in northern Alaska. Between the 10th and 12th centuries the culture had spread eastward to Greenland (Kalaallit Nunaat) and then, from approximately 1300 to 1700 AD the Thule people migrated into the central areas of Arctic Canada.

Maps showing the different cultures in Greenland, Labrador, Newfoundland and the Canadian arctic islands in the years 900 AD, 1100 AD, 1300 AD and 1500 AD. The green color shows the Dorset Culture, blue the Thule Culture, red Norse Culture, yellow Innu and orange Beothuk. (CC BY-SA 3.0)

The Thule people adapted to the harsh Arctic environment by hunting large sea mammals in open water with drag floats attached to harpoon lines. They built large skin boats and used dogs to pull large sleds, and both of these skills accelerated rapid migration and transportation of the Thule culture eastward. As a result of their eastward migration, they replaced the Paleo-Eskimo Dorset culture and interacted with the Vikings of Norway.

Maritime Hunting And Settlements

The Thule culture hunting technologies included slate knives, umiaks, and kayaks for hunting seals, walrus and whales, and their iconic toggling harpoons were favored in bowhead whale and sea mammal hunting. Made from antler, bone and ivory the earliest known toggling harpoon head was found at a 7,000-year-old Red Paint burial site in Labrador, at the L'Anse Amour Site. Comprising of two parts, one half of the point is firmly attached to the thrusting base while the second half of the point is fitted over the first point, like a cap, and attached to the rest of the point with line of sinew-string. Once this harpoon was thrust into an animal the toggle end of the harpoon lodged under the animal’s skin and blubber making it almost impossible for the harpoon to dislodge. Over time inflated harpoon line floats were added to toggling harpoons so to create a drag, or resistance, so Thule hunting groups could pursue and hunt larger prey, such as whales, over several days or weeks.

Mostly located near the seashore, the Thule people built snow-houses during winter journeys which served as hunting stations in the summer. Whales, walrus, seals, polar bears, caribou, birds, fish, mussels, and wild plants were prepared in these structures and during winters large communities inhabited semi-subterranean houses. Surviving on stores of bowhead whale meat that was caught and preserved though the summer, Thule winter settlements usually consisted of a combination of stone and whalebone covered with stones and sod, and they had between one and four houses per settlement. According to Dr Robert W. Park in his 2015 paper Thule Tradition, an estimated ten Thule people lived in each house.

Inuit groups used a variety of materials, mostly animals skins, to manufacture their clothing and to make strong tents, and this was made evident at the mukluk recovered from the Birnirk site near Utqiagvik in Alaska. Designated a National Historic Landmark in 1962, this settlement comprises 16 prehistoric mounds in which evidence of early Birnirk and Thule culture has been discovered. Scientific excavations were made at this site in 1936 and again in 1951-53, when three mounds were excavated. Then, in 1959, seven further mounds were partially excavated, and while all of these structures were created by the Birnirk culture, between 500 and 900 AD, Thule culture artifacts were discovered dating to 1100-1400 AD, determining they reused this site.

All terrestrial and marine animal species were hunted but individual seal hunting in particular, played a major role in Thule culture communities, while whaling and caribou hunting were more complicated communal activities involving much more strategic co-operation among the hunting teams. Fishing was an important supplement to subsistence and increased in South Greenland, while polar bears were traditionally hunted in northernmost West Greenland. On the east coast the hunting of wintering birds on the ice-free waters of Southwest Greenland took over all hunting activities as the climate cooled during the 17th and 18th centuries.

Trading And Warring

The trade and exchange economy of the Thule culture in the 13th century brought them into contact with the Dorset people and Norse populations. Historian Hans Christian Gulløv´s 1997 book From Middle Ages to Colonial Times. Archaeological and ethnohistorical studies of the Thule Culture in Southwest Greenland 1300 – 1800 AD informs that 17th-century written sources mention Inuit trading expeditions along the European whaling grounds on the west coast of Greenland, as well as intra-group marriage and the exchange of soapstone, caribou skin, baleen and driftwood. Evidence of warfare among Thule culture groups occurred due to resource competition or raiding of other groups. According to Gulløv both copper and ivory slat armor plates have been recovered suggesting conflict among groups was not uncommon and may have been long-standing.

Game Changer: Cape York Meteorite

In 2016 Dr Bathsheba from Brown University published What Made the Thule Move? Climate and Culture in the High Arctic? which postulates traditional views associated the rapid Thule expansion with the Medieval Warm Period in the years between 1000 and 1300 AD. However, 21st-century research has totally changed this interpretation of Thule migration and in 2000 Dr Robert McGhee proposed the 1200s as the earliest date of Thule culture migration. This idea was supported by the findings of genetic tests that showed Atlantic and Pacific bowhead whales did not mix their populations during the Medieval Warm Period, meaning that there was a substantial gap in whaling possibilities on the Arctic coast. Something more complicated than just following the blubber, had driven the Thule eastward and Dr McGhee further speculates that communities moved in search of iron, which was short supply in the Arctic. The researcher concluded that: “Thule hunters learned from the Dorset people of a deposit of iron left by the Cape York meteorite, and they colonized huge territories to secure their access to this precious resource from outer space.”

Believed to have crashed to earth around 1000 AD, the Cape York meteorite, also known as the Innaanganeq meteorite, represents one of the largest known iron meteorites to have crashed into North America. Coming onto the earth’s atmosphere the space rock broke into eight large fragments with an estimated total mass of 58 tons and it was named after the location where the largest fragment was found: 23 miles (37 kilometer) east of Cape York, in Savissivik, Meteorite Island, Greenland. This iron-loaded cosmic visitor was known to the Inuits for at least six centuries and archaeologists have discovered weapons and hunting tools made from meteoritic iron. The first westerner to recover pieces of this history-changing meteorite was Robert Peary in 1894, and large pieces are on display at the American Museum of Natural History and the University of Copenhagen Geological Museum.

Medieval Warm Period

Canadian archaeologists T. Max Friesen and Charles D. Arnold confirmed “that we must look beyond simple climatic explanations for the Thule expansion” and they suggest the Thule civilization only began its continental spread around the year 1200 AD, well into the period of warming. The climate may have helped the Thule’s rapid spread towards Greenland, but the onset of the Medieval Warm Period did not automatically draw people eastward, they concluded. Furthering this line of thinking archaeological work by professors Finkelstein, Ross, and Adams, on the Melville Peninsula in Baffin Bay, indicate that the Medieval Warm Period was not always so warm and that some areas of the Arctic saw slight temperature increases, but in general the millennium was cooler than previous ones. Thule people, according to this study, adapted not to a warmer Arctic, but a colder one and their move into the central Arctic in this view, reflected greater forces than only climate change.

By the beginning of the 15th century the ancient Thule culture began fragmenting into contemporary Inuit and Inupiat groups, and their increased contact with European explorers brought in a host of new infectious diseases that their immune systems had no resistance to. It was these microbial invaders that ultimately led to the demise of the Thule people as a distinct cultural group, but many of their traditions live on today in indigenous Alaskan communities.

Ashley Cowie is a Scottish historian, author and documentary filmmaker presenting original perspectives on historical problems, in accessible and exciting ways. His books, articles and television shows explore lost cultures and kingdoms, ancient crafts and artifacts, symbols and architecture, myths and legends telling thought-provoking stories which together offer insights into our shared social history. www.ashleycowie.com.

https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/thule-culture

True Civilization Sites Predating the Neolithic Revolution

The famous Tower of Jericho at Tell es-Sultan archaeological site was constructed around 8000 BC. (Public Domain)

The beginnings of what archaeologists often call ‘true civilization’ are most often attributed to the Neolithic Revolution, which began at different places around the world from around 10,000 BC. It marked one of the most important periods in human history when nomadic hunter-gatherer-fisher ancestors began settling as new agricultural methodologies were being developed. However, while most of the earliest known human settlements date back to the Neolithic, a collection of the archaeological sites predates them by sometimes tens of thousands of years and contain some of the earliest works of art on the planet. ‘True civilization’ could have been born long before the Neolithic Revolution.

Tell es-Sultan Jericho

Age: c. 9000 BC; Location: Jericho, West Bank, Palestine; Discovered: 1868; Primary Use: Fortified settlement.

Scatterlings of flint tools and the remains of mudbrick houses were discovered in 1868 at Tell es-Sultan, also known as Tel Jericho, the site of Biblical Jericho which is today a UNESCO-nominated archaeological site on the West Bank, located two kilometers north of the center of Jericho. Inhabited from the 10th millennium BC this settlement is often referred to as ‘the oldest town in the world’ and during the Younger Dryas stadial, of colder climates and droughts, Tell es-Sultan was a popular camping ground for Natufian hunter-gatherer groups. According to Steven Mithen in his 2006 book After the ice: a global human history, 20,000-5000 BC this particular site was of great value because of the nearby Ein es-Sultan spring, around which ancient hunter-gatherers left tiny crescent-shaped microlith tools.

Around 9600 BC the droughts and cold weather of the Younger Dryas period began to end allowing Natufian hunting groups to live at this site all year-round and a permanent settlement was founded. Archaeologists have found evidence to suggest epipaleolithic construction at Jericho predates the invention or development of agriculture, with these Natufian structures dating to before 9000 BC at what was the beginning of the Holocene epoch in geologic history. During the Pre-Pottery Neolithic A (PPNA) phase at Tell es-Sultan (ca. 8500 – 7500 BC) one of the world's first major proto-cities emerged and the PPNA-era settlement measures around 40,000 square meters (430,000 square feet), containing round clay and straw, mud-brick houses, plastered together with a mud mortar. Each dwelling measured about five meters (16 feet) across. By 7000 BC Tell es-Sultan had become a large, fortified town and it was around this occupation that the famous wall and tower of Jericho were built to protect the settlement.

The massive wall and tower were built around 8000 BC and at its base it measures 1.8 meters (five feet 11 inches) wide, inside of which, a stone tower was built in the center of the west side of the tell, which represented the world’s tallest structure until the construction of the Pyramid of Djoser in Egypt, for the burial of Pharaoh Djoser, during the 27th century BC. Archaeologists radiocarbon dated the tower in 1981 and 1983 indicating that it was built around 8300 BC and stayed in use until ca. 7800 BC. It is estimated that using stone tools the wall and tower took 100 men more than 100 days to construct, which suggests some form of social organization and managed division of labor in deep prehistory.

Cave art, bison of Altamira, Spain (40,000 years BC)(Public Domain)

Altamira Cave, Spain

Age: c. 25,000 BC; Location: Santillana del Mar, Cantabria, Spain; Discovered: 1868; Primary Use: Cave settlement holding the oldest cave paintings in the world.

Located near the historic town of Santillana del Mar in Cantabria, Spain, around 13,000 years ago a rockfall sealed the Altamira cave's entrance and it was only in 1868 when a tree fell nearby and disturbed the fallen rocks when archaeologist Modesto Cubillas found the caves. Measuring approximately 1,000 meters (3,300 feet) long with a series of twisting passages and chambers, varying from two to six meters in height, according to a 2018 article, The discovery of Altamira, written by archaeologists at the Museo Nacional y Centro de Investigación de Altamira, the cave is renowned for its prehistoric parietal cave art featuring charcoal drawings and polychrome paintings of contemporary local fauna and human hands, the earliest of which date to over 36,000 years ago.

The Cave of Altamira, however, was not always a well-known or respected archaeological site. When it was first excavated in 1879 many scholars rejected the authenticity of the cave paintings because they were strikingly different from others discovered in France. It was only in 1902 that the site was finally taken seriously. Sadly in 2002 mold started to appear on some of the paintings which archaeologists put down to the use of artificial lights, and to control this, since 2014, only five lucky visitors a week are permitted to view the Altamira cave art up close wearing protective suits. While human occupation was limited to the cave mouth, paintings were created throughout its length with charcoal and red ochre, or hematite, and the now extinct steppe bison (Bison priscus) horses, deer and boar have been designed using the natural contours of the cave walls to give them a three-dimensional appearance.

Archaeological excavations in the cave floor have revealed a rich layer of artifacts dating from the Upper Solutrean period about 18,500 years ago and from the Lower Magdalenian between 16,590 and 14,000 years ago, and it is known that in the two millennia between these two occupation periods the cave had been inhabited by wild animals. It is thought that the early hunters chose to live in this particular cave because it is close to the valleys of the surrounding mountains, that were once filled with grazing wildlife, and they also had access to marine life in the nearby coastal areas.

Murujuga Australia

Age: c.28,000 BC; Location: Dampier Archipelago, Western Australia; Discovered: Protected by indigenous peoples for thousands of years; Primary Use: Sacred indigenous landscape with over a million petroglyphs.

Murujuga, most often called the Burrup Peninsula, is an island in the Dampier Archipelago, in the Pilbara region of Western Australia, and this sacred Aboriginal territory is home to some of the oldest petroglyphs (engraved rock art) in the world with at least a million individual works of art dating as far back as about 30,000 years ago, but archaeologists know the Aboriginals may have been living in the region for over 50,000 years.

Map of Dampier Archipelago and Burrup Peninsula, Western Australia. (Public Domain)

Australia has some of the world’s most diverse rock art. What is relatively unique is that cultural connections still exist between rock art and the people who created it. However, while France has over 30 World Heritage-listed rock art sites, Australia has only three, of which only one, Kakadu, is listed for rock art. The extraordinarily old engravings are located in a deeply ancient cultural landscape which has quarries and living settlements surrounded with shell middens, which according to an article in The Conversation illustrate significant transitions in human history in the face of major changes in sea level and surrounding environment.

When people first expanded across this landscape around 50,000 years ago it was located about 100 kilometers (62 miles) from the coast and the climate was much wetter and warmer than it is today. The fossils found on the coastal plains at this time demonstrate an entire group of animals no longer found in this part of Australia, and Murujuga’s ancient artists engraved some of these animals, such as crocodiles, thylacines and a fat-tailed kangaroo, which all record the changing environment.

As the ice caps slowly melted causing sea levels to rise, the people became more concentrated on new coastal landscapes and recent studies have demonstrated the scientific significance of islands in this new cultural seascape. By 6000 BC people began building stone houses, stone arrangements, standing stones and terraces and the most recent rock art includes creatures such as fish, dugong, turtles and rock wallabies and quolls that now live on the islands. The story told in the artworks of Murujuga tell how people have been surviving in the region for thousands of years, first as hunter-gatherers, and later with a focus on fishing.

Theopetra Cave in Central Greece contains not only the oldest human construction on earth, but it was inhabited as early as 130,000 years ago. (Tolis-3kala/CC BY-SA 4.0)

Theopetra Cave Greece

Age: c.133,000 BC; Location: Thessaly, Greece; Discovered: 1987; Primary Use: Cave settlement with oldest known human-made structure.

Following several decades of research and excavations, in 2012, archaeologists made the incredible discovery that humans had lived in Theopetra Cave, in the Meteora limestone rock formations of Thessaly, Central Greece, over 135,000 years ago making this the oldest archaeological site in the world. Several interesting archaeological discoveries have been made in Theopetra Cave, for example, micromorphological analysis on the sediment samples collected from each archaeological layer were analyzed to determine that there had been hot and cold spells during the cave’s occupation and that the cave’s population fluctuated with the changing climate.

Dr Aikaterini Kyparissi-Apostolika, head of the Ephorate of Palaeoanthroplogy and Speleaography of Greece’s Ministry of Culture and Sports, specializing in prehistoric archaeology and spelaeology, was the head of the team which began excavations in Theopetra Cave in 1987. In an article in Greek Reporter she describes Theopetra cave as being roughly quadrilateral in shape, with small niches on its periphery, covering an area of about 500 square meters (5,380 square feet). Archaeologists discovered a stone wall which once partially closed off the entrance of the cave, which researchers think had been built by the inhabitants of the cave to protect them from the cold outside. Using a dating technology called ‘Optically Stimulated Luminescence’, this wall has been dated to around 23,000 years old, which means it is the oldest known man-made structure in Greece, and possibly in the world.

A year before the wall was discovered hominid footprints were found imprinted on the cave’s soft mud floor, which were possibly made by a group of Neanderthal children aged between two and four years old during the Middle Paleolithic period. One of the most important finds inside Theopetra Cave were the remains of an 18-year-old woman who lived in Greece 7,000 years ago whom archaeologists have named Avgi (Dawn). Little is known about how Dawn lived or died, but a 2018 National Geographic article details how University of Athens archaeologists figured out that the ancient woman had prominent cheekbones, a heavy brow, and a dimpled chin and recreated a model of Avgi, which was unveiled at the Acropolis Museum in January 2018.

Each of these sites represent the oldest settlement, the oldest arts, the oldest walls and towers; and all are pre-Neolithic Revolution (10,000 BC) and each one is an archeological sentinel dragging back the origins of true civilization into a bygone ancient world, a world once inhabited by now extinct creatures which man’s modern forefathers hunted to extinction. In comparison, the Neolithic Revolution happened yesterday.

https://members.ancient-origins.net/articles/neolithic-revolution

No comments:

Post a Comment